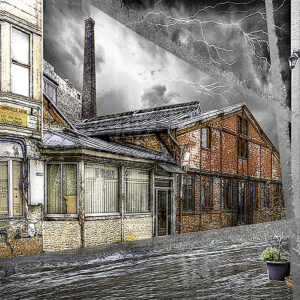

Far from mass tourism attractions, a narrow cobble-stoned Parisian alley tells us the story of carpenters who came from Holland and Germany during the sixteenth century to settle in the Saint-Antoine district. A hidden pathway possibly witnessing the “raison d’être” of a community: a stamp-varnishing master, a manufacture built in 1886 converted in artists’ studios, a former sawmill with one of the last square based brick chimney recalling the industrial heritage of the place.

With its holistic approach and the way it encompasses tangible, intangible, natural and even digital forms, cultural heritage cannot be simply seen as an exhaustive list of infrastructures, natural sites and/or cultural habits. It extends the definition of the word “heritage” to a conceptual approach questioning not only the legacy to future generations but also how the “past” can improve our well-living and wellbeing. Interestingly, bridging the past to present times has also implications on the resilience and sustainability of socio-ecological systems. Ancient practices of cultural burnings may contribute positively to decrease wild or urban fire risks (1) and historical city grid adaptations are not without consequences on urban resilience (2). However, stating that cultural heritage improves resilience raises a certain number of questions. Coming back to our cobble-stoned alley which will need to face climate change consequences, can we say that it will cope, adapt or respond in any way that could maintain its identity? And if so, how would this contribute to improve the well-living and wellbeing of the lucky ones living there?

The publication of C. Holtorf (3), Embracing change: how cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage, raises the topic in a way that some could find controversial but which has the merit of clarity. The author argues that to be resilient, cultural heritage needs to be adaptable and receptive for transformations. “Cultural heritage that has persisted to the present day can tell powerful stories about transformation over time. The question is not whether some of it is gone, together with the times that are gone, but how much of it has developed and adapted to new realities.” Whether such statement bears a universal truth is questionable and giving as an example of resilience the empty niches of the destroyed Buddha statues in Afghanistan as “having absorbed the Taliban iconoclasm and radical extremism” may hurt. However, stating that tribal traditions could oppose social groups to others and stressing the resilience potential of our multiple collective identities no matter who our ancestors are, feed some fruitful thoughts.

Amongst the different components liable to improve socio-ecological resilience, there is a clear consensus on the importance of “the sense of place”. Sense of place can be defined as the way individuals are connected to a place. More than the place itself, what matters here are the appropriation process and its dynamics building the connections between people and their living environment. N. Frantzeskaki & Al. (4) describe three key phenomena linking urban resilience to the “sense of place”, as follows: 1. The way urban experiments contribute to social relations and networks between people and the place; 2. The way narratives introduce a transformative vision; -3. The symbolic meaning of the place leading to a sense of belonging. Seen from this perspective, cultural heritage can undoubtedly improve urban resilience.

In his publication, C. Holtorf recalls how understanding our origins and history may provide the psycho-social support in times of need, increasing a community’s capacity to absorb disturbance. But where are the evidences? When NMN Mohammad & Al. (5) review the factors contributing to the “sense of place” within the landscape of culture, emphasizing the subjectivity in the way we perceive our environment, they raise a fundamental issue: we cannot assume that the relation between urban cultural heritage and the “sense of place” would arise from an innate gift enabling urban citizens to build the connection with their living environment. The way historical dimension is perceived when cultural heritage is threatened by natural hazards is closely linked to governance, whether top-down or bottom-up. In such environment, improving mitigation has been reviewed by many authors (6). But the ability and willingness of all stakeholders, including dwellers, to implement the three key phenomena as above mentioned, will be much more challenging and cannot be taken as granted. Moreover, historical places do not always qualify as primary landmarks to be included in urban planning upgrading projects as recalled by the World Bank (7).

The memories of our cobble-stoned alley, engraved on the facade walls, speak of civil rights struggle that paved the way to democracy. They are not only asleep but also in danger. Are dwellers willing to wake them up, give them a new life? The below work emphasizes the risk of a cultural identity loss. Whether the gauze strips should be seen as a sign of healing or wounding remains a question mark.

- https://www.resi-city.com/2020/01/06/do-cities-learn-from-getting-burned/

- https://www.resi-city.com/2018/09/24/when-urban-resilience-deals-with-our-cultural-heritage/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11625-018-0562-5

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273425615_A_Sense_of_Place_within_the_Landscape_in_Cultural_Settings

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305900614000397

- https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/12286