The need to protect the so-called “tangible form” of our cultural heritage, such as historical monuments, has been recalled by notorious institutions (UNESCO 1972 General Conference, UN 2015 World Conference). Acknowledging the key role played by its conservation in preserving our identity, in strengthening the community cohesion and in developing sustainability has achieved a broad consensus. However well-intentioned this awareness may be, the way urban spaces will encompass the historical monuments aesthetics, as well as their relationship to the environment where they are located, seems to remain a pending question. Firstly, how should we define the value of our cultural heritage? According to D. Throsby (1), the cultural values of monuments, though not expressed in monetary terms, follow a comparable dynamic to any economic capital, enabling to analyze cultural values development with the same methodological tools. One of the findings will not surprise: economic and cultural evaluations of a project are only partially aligned. Trying to define the value of our historical heritage within a resilient and sustainable perspective could surprise. But heritage policies are deeply imbricated in urban strategies: conceiving their value is unavoidable when prioritizing actions. A perfect example is provided by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England, in charge of the sustainable management of historic environment (2). Their conservation principles, policies and guidance are perfectly well balanced taking into account the constraints of maintenance and sustainability. With one remarkable resilient statement page 46: In reality, our ability to judge the long-term impact of changes on the significance of a place is limited. Interventions may not perform as expected. As perceptions of significance evolve, future generations may not consider their effect on heritage values positive. It is therefore desirable that changes (…) are capable of being reversed, in order not unduly to prejudice options for the future.

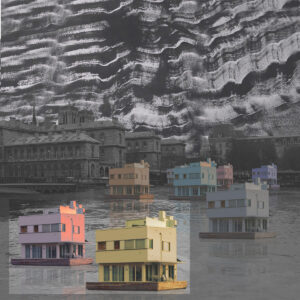

Amongst the different hazards that may disturb urban communities, one should deserve more attention: flooding in dense and historical city centers. Neither mitigation nor adaptation is easy. Elevating the first floor is not always technically feasible and waterproof materials can only partially contribute. Floating houses have proved to be very efficient in contemporary urban frames or in newly built cities. But how far are we ready to go in central districts along the Thames, the Arno or the Seine? Should we build levees to mitigate the risk? Should we start adapting the city urbanism when a 100 year flood is said to be unavoidable (3)? And at what cost for the current architecture? In other words, is a new cultural capital substitutable for old? Very cleverly, D. Throsby (4) recalls that the re-design of Paris by Haussmann in the 19th century, which has undoubtedly increased the architectural resilience of the city (5), involved the demolition of many buildings that would presumably have had some cultural value at the time of their disappearance, and would possibly continue to do so today, if they were still there.

Reaching a new state of balance helping to integrate the occurrence of flooding would make sense. But don’t we run the risk of destabilizing the city “imageability”, as defined by Kevin Lynch? (6). Paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks overlapping and piercing one another, play a predominant role in the city identity, structure and meaning. And as underscored by K. Lynch taking Florence as an example, p. 93, there seems to be a simple and automatic pleasure, a feeling of satisfaction, presence, and rightness, which arises from the mere sight of the city, or the chance to walk through its streets.

How far are we ready to go? The below work sounds like a warning, not to forget where we are coming from and the importance of legacy when we intend to build a sustainable urban environment for future generations.

More on the above photographic work can be found here

(1) Economics & Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2000

(2) https://www.historicengland.org.uk/

(3) https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/jun/23/paris-seine-flood-of-the-century-disaster

(4) http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSDNET/Resources/Economics_of_Uniqueness.pdf

(6) The image of the city, the MIT Press