The current pandemic sheds a new light on affordable housing and how it may strengthen urban resilience. The “stay home” injunction confronts with the political challenge to enforce moratorium on evictions and foreclosures. Adequate housing appears to be more than a standard of living with the raising awareness that it is a human right (1). But beyond such institutional statements, what is the meaning of housing? How does it connect to urban resilience? Is housing activism counterproductive when preventing retreat from flooding areas?

The current pandemic sheds a new light on affordable housing and how it may strengthen urban resilience. The “stay home” injunction confronts with the political challenge to enforce moratorium on evictions and foreclosures. Adequate housing appears to be more than a standard of living with the raising awareness that it is a human right (1). But beyond such institutional statements, what is the meaning of housing? How does it connect to urban resilience? Is housing activism counterproductive when preventing retreat from flooding areas?

L.J.Vale & Al, (2) address the issue of resilience recalling that housing must be conceptualized holistically as a way to help low-income residents to cope with the challenges of economic struggle, changing climate, urban violence, and dysfunctional governance. To this extent, housing needs to be understood as one piece of the urban puzzle intertwining with others, and not merely as a basic shelter. But the Covid 19 crisis raises much more fundamental questions, as very often when crisis force us to reconsider what is taken as granted. Though forced evictions are declared to be in full contravention with basic human rights, current regulations on property may well be again enforced when the pandemic is over. And there is a real concern that the recent report of the United Nations on the right to adequate housing (3) will come to nought. De facto, the current situation should engage us in some deeper thinking. What is the true meaning of housing?

In “Accumulation, Dispossession, and Debt” (4), P. Chakravartty & D. Ferreira da Silva inspire us to think about the way housing developed during the subprime crisis, highlighting a racial and post-colonial context, paving the way for a political approach embedded in an implicit disruption. The consequent radical proposals challenge the way academics may build on a transformative knowledge moving beyond individual commitment and institutional statements (5). In a deeply political urban context, the theories of change catalyze the awareness of unequal power dynamics and how they exclude low-income or disadvantaged communities. Highlighting the importance of a structured collaboration and co-learning process between research, social movements and institutions is more than welcome. And sharing the same values for such critical issues is crucial. But ultimately, what are the prospects for an improved urban resilience and over what time frame?

Inequalities are nested in a socio-political environment leading to constrained individual choices. Their systemic nature makes them difficult to be fully consciously assessed showing the imperative need for a critical thinking. A striking example is provided by the publication of M.K Alvarez (6) on benevolent evictions defined as a mode of dispossession whereby benevolence is deployed as a technology of eviction. In this paper, the author shows how a new governance involving citizen participation in a Manila slum resettlement program, “inspired” by institutional recommendations, ended up in unmanaged evictions. Justified by a social housing policy, informal settlers were relocated when not left homeless, as the eviction was key to implement a new local master plan. The way citizen participation was misused in such tokenistic approach helps to understand the emergence of movements seeking for radical social changes.

Informal settlements are not always doomed for failure as told by L. Algoed & M.E. Hernadez Torrales (7). In the year 2000s, thousands of Puerto Ricans established the first Community Land Trust in Latin America, a regulatory instrument aiming to disconnect the ground from its “structural improvements”, where the land is treated as a common heritage that can never be sold, permanently taken out the market. In a move anticipating the gentrification process accompanying on-site rehabilitation, dwellers protected their community from displacements occurring as a consequence of possible local urban reforms, and this for the generations to come.

What is affordable, for whom and for how long? ask L.J.Vale & Al.(2). Can we make sure that the answers help to solve the vulnerability of dwellers staying in slums? Living in so-called informal settlements is never a choice and too often disasters are used to justify unmanaged evictions. Housing activism may take the form of exclusionary resistance questioning its contribution to urban resilience; but up to what point can we accept that human rights are ignored on the ground of their incompatibility with a profit-driven neo-liberal logic? The number of conventional dwellings in Europe that were structurally vacant ten years ago was estimated at more than 38 million (8). Amongst them, how many are hold for speculative reasons, nurturing vulnerability for those of us being in need, leading to the dramatic increase of homelessness?

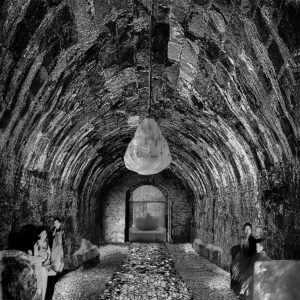

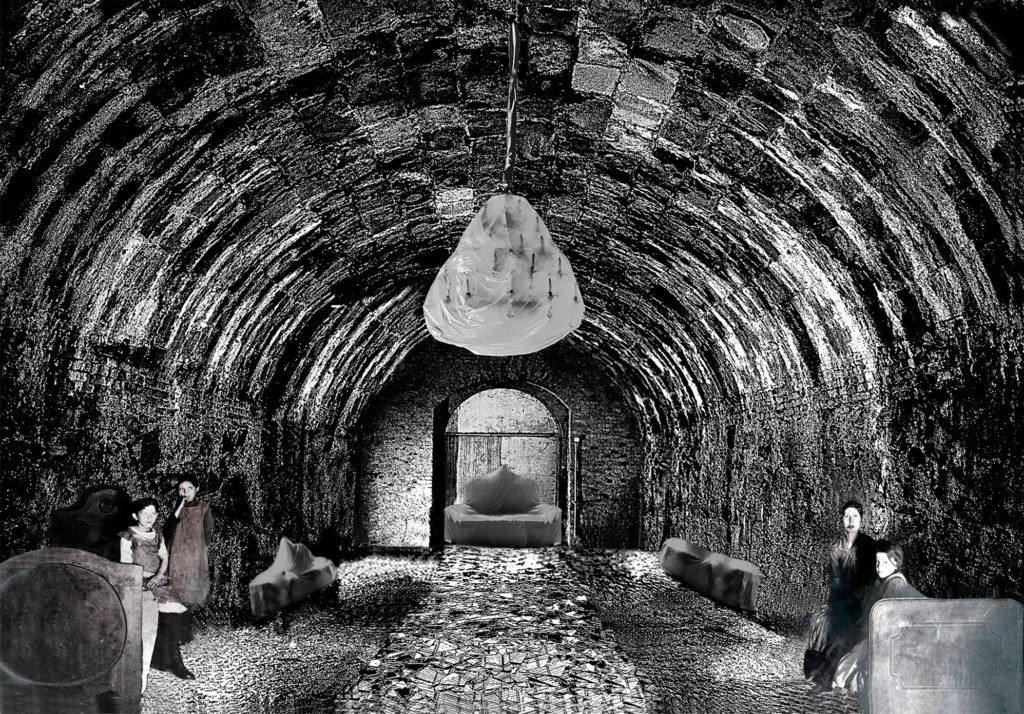

In the below work, radical housing is seen through the lens of an incongruity: holding legally a vacant private property for speculative reasons when illegal requisitioning could save people lives.

- https://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/26326882

- https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/housing/pages/housingindex.aspx

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265709826

- https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/02/04/co-producing-knowledge-with-social-movements-a-critical-perspective/

- https://radicalhousingjournal.org/2019/benevolent-evictions/

- https://radicalhousingjournal.org/2019/the-land-is-ours/

- https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/sites/futurium/files/long_version_en.pdf.pdf